Introduction

After spending some time at the start of my career working on user interfaces, I got really interested in the impact of error on a user’s ability to get the most out of a system.

As a really simple example, if the user has to enter an ISO currency code, a plain text box would suffice:

But if you misremembered or mistyped the currency code, you wouldn’t know until whatever was behind the text box told you (or until you submitted the form; or maybe not at all).

Even if the UI surfaces an error message when the currency is incorrect, you still had to type out the wrong thing before knowing it’s wrong.

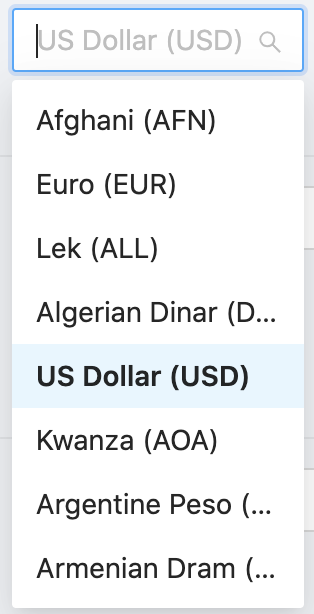

Instead, you could provide a searchable list of currencies:

This restricts the input to only acceptable values as early as physically possible - before the user has typed anything at all - but not so early that you get an error before you’ve even finished typing, which is also very annoying.

So our change has made our system subtly more efficient (and empowering) to use.

Applying UX principles to coding

One of the best things about TypeScript is that it allows you to apply similar principles to writing code, and design out the possibility of developer errors analogous to the user input errors we saw above.

The rest of this post will sketch out a more involved example of this process.

The Price Aggregator example

Imagine you’re working on a system which is like one of those price aggregator websites that you might use when you’re renewing your insurance. You put in some details, and the website will search a variety of different providers and come back to you with a list of options.

The request it makes may fail for any number of different reasons, many of which are to do with the third parties the system relies on and not the fault of the system itself.

A pseudo-skeleton of the code might look like this:

const server = require('your-favourite-http-server')();

server.post('/search', async (req, res) => {

const { search } = req.body;

if (!isPermitted(search)) {

return res.forbidden();

}

if (isTooManyRequests(search)) {

return res.tooManyRequests();

}

return runSearch(search).catch((e) => res.internalServerError(e.message));

});

Monitoring our system

In your system, the business people want to be able to monitor the causes of different types of failure in a business-friendly way so that you can get a quick visual understanding of the throughput of the system. With hundreds of providers and searches, being able to visualise how the system is doing in this way is crucial.

So you introduce a framework for sending events to an external system as they happen, via a Monitor interface with a register() method, which allows you to record that a particular type of event occurred, and add key-value pairs (“tags”) with metadata about the event.

interface Monitor {

register(event: string, tags: { [k: string]: string }): void;

}

(What the monitor actually does would depend on the system implementation: it could send events to a data warehouse, or plug into a cloud monitoring solution like Datadog, or just output structured logs.)

Here’s what the server code might look like with this monitoring:

server.post('/search/v2', async (req, res) => {

const { search } = req.body;

if (!isPermitted(search)) {

monitor.register('search-v2.request-received', {

outcome: 'forbidden',

location: search.location,

});

return res.forbidden();

}

if (isTooManyRequests(search)) {

monitor.register('search-v2.request-received', {

outcome: 'rate-limited',

location: search.location,

});

return res.tooManyRequests();

}

try {

const result = await runSearch(search);

monitor.register('search-v2.request-received', {

outcome: 'success',

location: search.location,

});

return result;

} catch (e) {

monitor.register('search-v2.request-received', {

outcome: 'error',

location: search.location,

});

return res.internalServerError(e.message);

}

});

This is great. We can filter by business-level outcome, and also by location. When this is running at scale, we’ll be able to stand up some real-time graphs of throughput during the system, and with alerting in place we’ll know quickly when something changes and be able to react to it.

But from a code quality and ease of development perspective, things aren’t so rosy.

Duplication

For starters, to register a new event, you have to type out quite a lot of code. Which means there’s a risk of typos!

For example, consider this nearly identical code:

monitor.register('search_v2.request_received', {

outcome: 'successful',

searchLocation: search.location,

});

Notice I accidentally used underscores instead of dashes, so all the events from this code path would be omitted from our throughput graphs.

Even worse, the outcome of successful is different from the success we enjoyed previously; and location has changed to searchLocation, so any attempt to filter by one would incorrectly exclude the events from the other.

At best, we’ll just have a clean break in the data - but we could also end up with inconsistencies which make it difficult to get any insight from these monitors at all. At worst, we might not even spot the errors and just draw incorrect conclusions from the data!

Union types to the rescue

This is where TypeScript comes in handy. Without changing the API of the monitor.register() method, we can restrict the inputs to the function at compile time to eliminate the chance of a typo or a misremembered term.

A simple way to so this for the event name would be to use a string union type:

type Event = 'search-v2.request-received' | 'searchv2.some-other-system-event';

// ... and many more ...

interface Monitor {

register(event: Event, tags: { [k: string]: string }): void;

}

This has two advantages - not only will it be a compile error if you misspell the event name, but many IDEs with IntelliSense-type systems such as VS Code and WebStorm will give you autocomplete options for the parameter if you hit Ctrl+Space, saving a bunch of keystrokes in the first place.

What about the tags?

This squashes one-third of our possible source of bugs. But we still have two more to go. For instance, notice that it’s still possible to misspell keys or values in the tags.

To get around this, we can declare an object type literal for the tags object, and another string union type on the outcome:

type Event = 'search-v2.request-received' | 'searchv2.some-other-system-event';

// ... and many more ...

type Tags = {

outcome: 'success' | 'rate-limited' | 'forbidden' | 'error';

location: string;

};

interface Monitor {

register(event: Event, tags: Tags): void;

}

We’ve now got covered all the possible sources of typos at compile time!

Tripping over our types

This solution has one major drawback: it assumes that our key-value tags are always the same for any event. However, the monitor is actually used elsewhere in the system for different types of events with different tags.

Here’s one on an analytics endpoint.

monitor.register('campaign-v3.impression', {

source: 'organic',

campaignCode: 3,

experiment: 'visible',

});

Nobody quite knows what it means or does, but it’s absolutely critical to the marketing department, so it needs to stay - and with our new typings, this code will no longer compile.

Towards a generic solution

Our type safety has become a type straitjacket. To solve this, we’ll need to combine some powerful TypeScript features: constrained generics, keyof and lookup types.

type Events = {

'search-v2.request-received': {

outcome: 'success' | 'rate-limited' | 'forbidden' | 'error';

location: string;

};

'campaign-v3.impression': {

source: 'organic' | 'search' | 'inquiry' | 'unknown';

campaignCode: number;

experiment: 'visible' | 'hidden';

};

};

interface Monitor {

register<E extends keyof Events>(event: E, tags: Events[E]): void;

}

The event parameter is now of type E, which can be anything that is a key of the Events type - that’s our event names from earlier.

Because it’s now a generic type, it resolves separately for each call of the method. This means that TypeScript will infer E to be whichever event name is the first parameter. Events[E] is a lookup type - it is the same square-bracket syntax as looking up a value in a JavaScript object, but here it’s in the type declaration space.

It works - we now have type safety and autocomplete over both events!

Is this really necessary?

As often happens, when I was implementing something similar to this across the system I work on, I suddenly realised that although it’s a neat, clean and extensible solution, it might not be the simplest.

An alternative is to dispose with the fancy mapped types and create one method per event on the Monitor.

class Monitor {

registerRequest(

outcome: 'success' | 'rate-limited' | 'forbidden' | 'error',

location: string,

): void {

this.register('search-v2.request-received', {

outcome,

location,

});

}

registerImpression(

source: 'organic' | 'search' | 'inquiry' | 'unknown',

campaignCode: number,

experiment: 'visible' | 'hidden',

): void {

this.register('search-v2.request-received', {

source,

campaignCode,

meta,

});

}

private register(event: string, tags: { [k: string]: string }) {

// don't need type safety here anymore

// because it's a private method now

}

}

Ultimately, it’s a value judgment and which one you go for will depend on the context of the system as well as your personal preference. I like the former because it’s easier to see what’s going on (the event name isn’t hidden), it’s a bit more declarative, and it’s more idiomatic JavaScript, even if it does result in more verbose code at the call sites.

But the one-method-per-event solution definitely has advantages too. For instance, it produces much easier-to-understand compilation errors, especially on the tags.

In Sum

When you have a system with lots of values known at build time, TypeScript offers a few great ways of increasing your productivity and reducing the chances of error whilst retaining the flexibility and familiarity of JavaScript syntax.